Old Abstraction, 2012, Petra Rinck Galerie, Düsseldorf

Old Abstraction, 2012, Installation view

Old Abstraction, 2012, Installation view

Old Abstraction, 2012, Installation view

Andy Warhol Display, 2012, Mixed media, silver gelatin

on baryt paper, life-size

on baryt paper, life-size

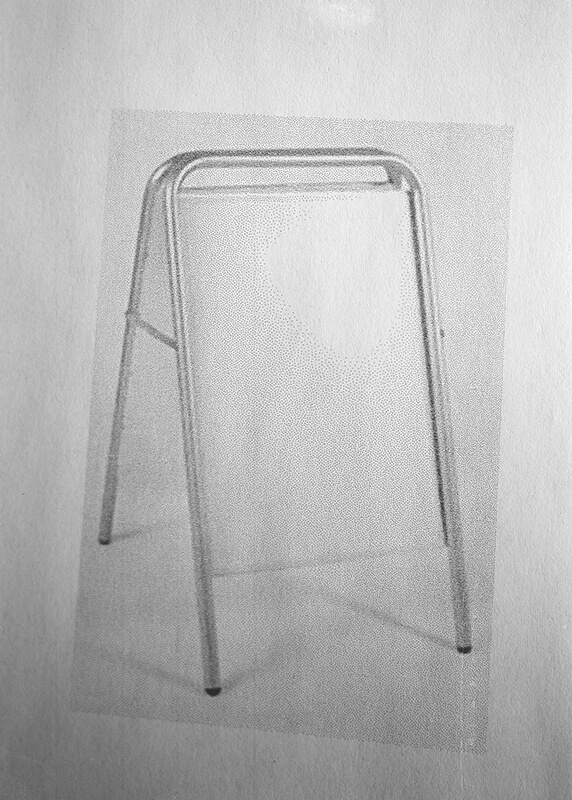

B-Display, 2012, Mixed media,

55 x 60 x 130 cm

H- Display, 2012, Mixed media,

67 x 56 x 21cm

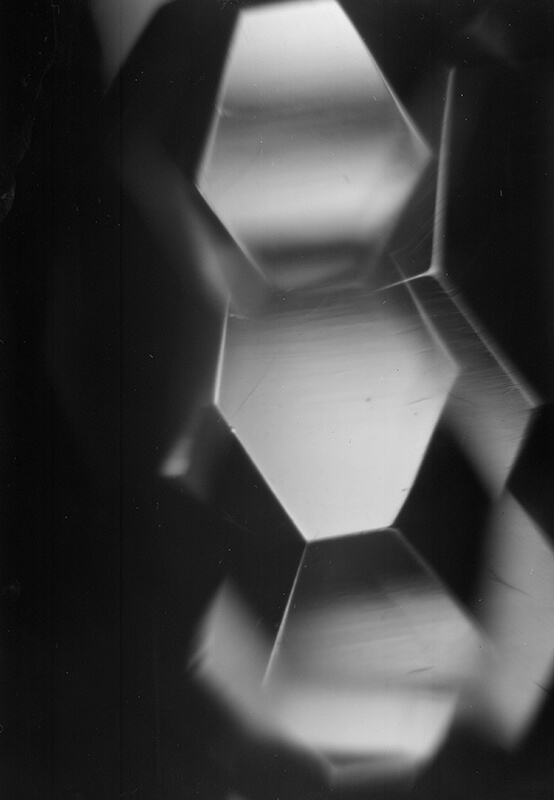

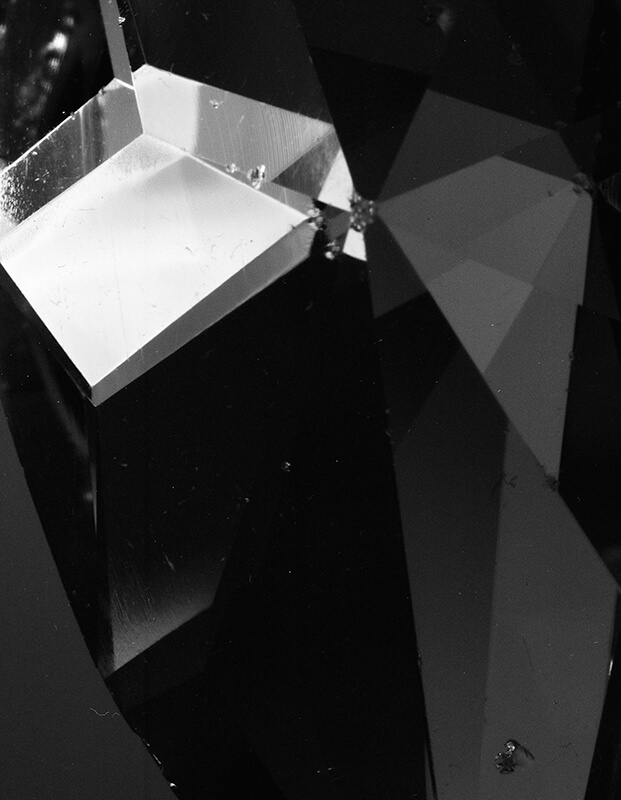

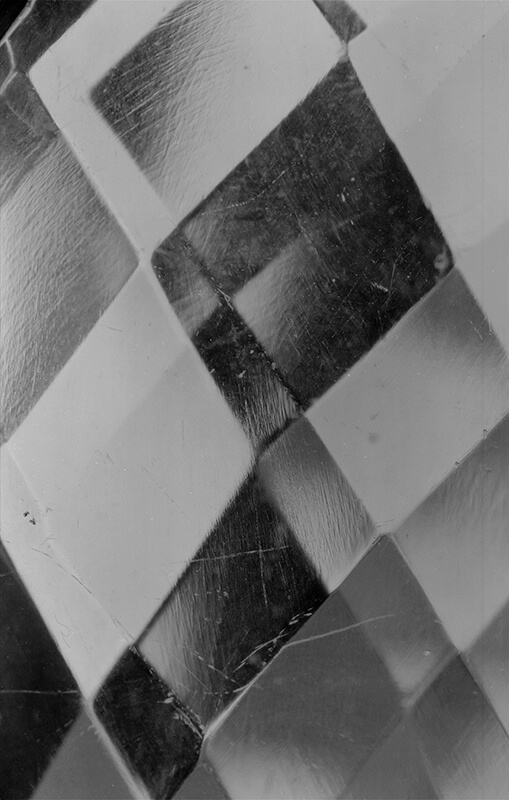

Untitled, 2012, Silver gelatin mounted on aluminium, 110 x 152 cm

Untitled, 2012, Silver gelatin mounted on aluminium, 110 x 152 cm

Beachflag, 2012, Mixed media,

30 x 30 x 200 cm

A-display, 2012, Silver gelatin mounted on aluminium, 80 x 115 cm

Untitled, 2012, Silver gelatin mounted on aluminium,

76 x 124 cm

76 x 124 cm

Untitled, 2011, Silver gelatin mounted on aluminium, 110 x 152 cm

Les Paul Display, 2012, Paper mache,

115 x 210 cm

Rolltreppen, 2011, Silver gelatin on baryt paper,

30 x 42 cm

OLD ABSTRACTION

John Miller

Napoleon in Rags

Since Andreas Wegner is known for working primarily outside the gallery context, this show marks a departure. The title signals this and, as a poetic/polemical construct, is as significant as the works per se. The phrase “old abstraction” presents itself as an unwanted appellation, the exact obverse of “new abstraction” – a claim used again and again to valorize an otherwise static practice of abstract art. Its awkwardness rubs up against a sense of fashion as the eternal return of the same and, by extension, capital’s ongoing abstraction of value from labor, the critique of which neo-liberals are so eager to foreclose. Who wants yesterday’s papers? A new show demands new work, ideally executed in a new style, or, at the very least, in a new variation of a previous style. Wegner confounds this with an array of photos and sculpture that incongruously resonate with various period styles. He coordinates all with an simple color scheme: black and white, accented with brown. Yet the set of relationships Wegner proposes is uncannily familiar: postmodern pastiche as conundrum. Dan Graham discussed just such an approach in his analysis of Robert Venturi’s interior design for the Capital Management offices in Philadelphia. There, the architect combined Art Deco and Chippendale lamps, couches and chairs withcontemporary office furniture. Graham argued that in so doing Venturi converted the office into a quasi-museological container with displaced artifacts. Wegner’s artifacts, too, are homeless, splitting the difference between what they represent and what they are. Yet, unlike Venturi’s office design, a certain surreality runs through the ensemble. In terms of scale, the most striking work in the show is Die größte Weihnachtskugel der Welt I (2012), a large functional lamp in which a 40 cm globe hangs from an inverted U-shaped frame. Wegner set it just behind the gallery’s storefront window so that people can easily see it from the street. The lamp has a vaguely Art Nouveau feel. If one peers in through the gallery window from the sidewalk, one cannot help but notice a second lamp, similar but not identical to the first, in the back room: Die größte Weihnachtskugel der Welt II (2012). Here too, the title counts. It implies the negation of the first lamp’s preeminence, qualifying, if not entirely seriously, how to take such redundant claims. Since almost every pizza parlor in New York City claims to offer “the world’s best pizza,” why not do something similar lamp-wise? Except Wegner claims them as Christmas ornaments. Because both lamps could work either as small streetlight or as an oversize floor lamp, they seemingly conflate public and private space. If indeed the lamp is to be used indoors, its oversized-ness connotes a very 1980s appeal to opulence. Yet, however tempting it may be to reduce the vulgarity of that period to a cliché, its residual complexity remains unresolved and disconcerting, as Robert Nickas recently observed: “The demonizing of that decade is an old, well-worn story by now, usually related by those for whom it has no lived texture, a time they may not have passed through, the wafting of so much second-hand smoke.” ... Display Andy Warhol (2011) is Wegner’s most aggressive work. For this, the artist cobbled together a mannequin from disparate limbs, fused them to a mass of Styrofoam and construction foam and topp. The photographic head, featuring Warhol’s trademark eyeglasses, resonates with Brillen’s subtle allusion to aging and infirmity. Since the mannequins legs are sleek – and painted black, like tights – and since garment, such as it is, is so ill-fitting, the mannequin also reads as a transvestite. This inevitably recalls Duchamp’s Rrose Selavy mannequin, which was a self-portrait or an alter ego. Display Andy Wahrhol likewise may be Wegner’s artistic self-portrait. On this occasion at least, like Warhol, Wegner confronts viewers with the artifacts of commerce and industry. Unlike Warhol, he refuses to synthesize these as a seductive, new style. Instead, he prefers to leave viewers to their own devices.

Extract of "Napoleon in Rags“, John Miller, first published in Texte zur Kunst, Issue 34/2012

John Miller

Napoleon in Rags

Since Andreas Wegner is known for working primarily outside the gallery context, this show marks a departure. The title signals this and, as a poetic/polemical construct, is as significant as the works per se. The phrase “old abstraction” presents itself as an unwanted appellation, the exact obverse of “new abstraction” – a claim used again and again to valorize an otherwise static practice of abstract art. Its awkwardness rubs up against a sense of fashion as the eternal return of the same and, by extension, capital’s ongoing abstraction of value from labor, the critique of which neo-liberals are so eager to foreclose. Who wants yesterday’s papers? A new show demands new work, ideally executed in a new style, or, at the very least, in a new variation of a previous style. Wegner confounds this with an array of photos and sculpture that incongruously resonate with various period styles. He coordinates all with an simple color scheme: black and white, accented with brown. Yet the set of relationships Wegner proposes is uncannily familiar: postmodern pastiche as conundrum. Dan Graham discussed just such an approach in his analysis of Robert Venturi’s interior design for the Capital Management offices in Philadelphia. There, the architect combined Art Deco and Chippendale lamps, couches and chairs withcontemporary office furniture. Graham argued that in so doing Venturi converted the office into a quasi-museological container with displaced artifacts. Wegner’s artifacts, too, are homeless, splitting the difference between what they represent and what they are. Yet, unlike Venturi’s office design, a certain surreality runs through the ensemble. In terms of scale, the most striking work in the show is Die größte Weihnachtskugel der Welt I (2012), a large functional lamp in which a 40 cm globe hangs from an inverted U-shaped frame. Wegner set it just behind the gallery’s storefront window so that people can easily see it from the street. The lamp has a vaguely Art Nouveau feel. If one peers in through the gallery window from the sidewalk, one cannot help but notice a second lamp, similar but not identical to the first, in the back room: Die größte Weihnachtskugel der Welt II (2012). Here too, the title counts. It implies the negation of the first lamp’s preeminence, qualifying, if not entirely seriously, how to take such redundant claims. Since almost every pizza parlor in New York City claims to offer “the world’s best pizza,” why not do something similar lamp-wise? Except Wegner claims them as Christmas ornaments. Because both lamps could work either as small streetlight or as an oversize floor lamp, they seemingly conflate public and private space. If indeed the lamp is to be used indoors, its oversized-ness connotes a very 1980s appeal to opulence. Yet, however tempting it may be to reduce the vulgarity of that period to a cliché, its residual complexity remains unresolved and disconcerting, as Robert Nickas recently observed: “The demonizing of that decade is an old, well-worn story by now, usually related by those for whom it has no lived texture, a time they may not have passed through, the wafting of so much second-hand smoke.” ... Display Andy Warhol (2011) is Wegner’s most aggressive work. For this, the artist cobbled together a mannequin from disparate limbs, fused them to a mass of Styrofoam and construction foam and topp. The photographic head, featuring Warhol’s trademark eyeglasses, resonates with Brillen’s subtle allusion to aging and infirmity. Since the mannequins legs are sleek – and painted black, like tights – and since garment, such as it is, is so ill-fitting, the mannequin also reads as a transvestite. This inevitably recalls Duchamp’s Rrose Selavy mannequin, which was a self-portrait or an alter ego. Display Andy Wahrhol likewise may be Wegner’s artistic self-portrait. On this occasion at least, like Warhol, Wegner confronts viewers with the artifacts of commerce and industry. Unlike Warhol, he refuses to synthesize these as a seductive, new style. Instead, he prefers to leave viewers to their own devices.

Extract of "Napoleon in Rags“, John Miller, first published in Texte zur Kunst, Issue 34/2012